The following article was published in the Macon Telegraph, Macon, Georgia, sometime in the 1930's and was transcribed by Suzanne Forte (suzanneforte@windstream.net), from information provided by Benny Hawthorne, December 2004.

Article written by Susan Myrick

"FIVE SISTERS LEAD PIONEER LIVES"

"Maiden Sisters Living Near Hillsboro Do all Work on Their Farm, Ploughing, Harvesting, Wood Cutting at Advances Ages - Oldest Is Eighty Three and the "Baby" is Seventy-Three"

"This is the day of equal rights, but there are few women who really want the right and privileges enjoyed by the "Jackson Girls", five maiden sisters, who live near Hillsboro and who have done all the ploughing, rail splitting, harvesting, planting, wood cutting and stock feeding, as well as the milking, cooking and washing, for many years. Just how many it is hard to say, for since their father "went away" to the Civil War, there has not been a man on the place.

The eldest sister is 83 and the baby is 73, and they are all active and able except the eldest, who had a stroke a few months ago and spends the greater part of her time in a rocking chair.

After driving down a dozen different roads, in vain effort to locate their house, I came upon a group of Negroes digging a grave in a lonely country churchyard and prevailed upon one of them to ride on the running board to show me where to turn off. He rode a mile or two, showed me a path which rambled through an old field, twisting and turning to avoid the pine trees and stumps, and told me to "drive rate on down dat road wen her git's ter Mistah Rich Garland's place, over dah bout half a mile, den you drive rate on pas' de house an' you see er tater patch on do lef', an' de road forks rat dah. You takes de lef an' de white ladies lives bout er half er a quarter mile down de straight road."

Carefully following directions, lurching and bumping in second gear, dodging stones and trees and bushes, wishing I had taken the other rut, which ever one I selected. I finally arrived at the place where lived the "Jackson Sisters".

A rambling rail fence surrounded the place, the kind commonly known as a worm fence, and a gate closed against intruders, was leisurely guarded by a large black hound dog. Bending over the wash pot in the front yard was an old lady with snowy hair, a dress which reached to the ground and an old fashioned sun bonnet which completely shielded her face from the sun and observation.

She came at once toward the gate, shying, a stone(?), meanwhile at the dog in order to induce him to do his duty toward guarding the place from intruders, but on being informed to the nature of our visit, and recognizing the Hillsboro lady with me, as the daughter of an old acquaintance, she opened the gate and put the watch dog "at east".

"Ya'll come in", she invited hospitably and led the way onto a porch cluttered with boxes in which the dogs were wont to sleep, festooned with strings of red pepper pods and decorated with various tin cans within which small green shoots struggled to bring beauty into a drab world.

"Rat in that room," she urged, and opened the door for us. We entered a large room, lighted only by the open door on the opposite side and the one which we had left open as we came in, for the only window was shuttered by a heavy wooden blind, and was minus any sort of sash or window glass.

The pine floor had been washed white with many scourings and the two beds which stood in opposite corners of the room were beautiful examples of furniture of a generation agone: one a spool bed, the other a hand carved four-poster, and both were adorned with coverlids of hand woven beauty which made me gasp.

Seated in her chair before the whitewashed fire place was Miss Julie, the eldest, partially paralyzed, patient and sweet. She is a pretty old lady with a face remarkably free from wrinkles and a skin which showed clearly that she was a beauty in her younger days. Her hair is not very gray, despite her three score and twenty years and it was easy to see that her sisters gave her patient and loving care.

Miss Lucy, for it was she who had met us, performed the intruductions simply by saying "Julie, here's some ladies come out to see us" and then she found chairs for us all.

Almost immediately, there entered the room, Miss Marjie, herself, white haired and clad in garments which reached to her feet and were obviously home made and of the style of our grandmothers. In fact, the entire sisterhood scorn modern styles and the foolish fancies of fashionable dress.

In her mouth, Miss Marjie wore a tooth-brush of the sort affected by snuff dippers and when she smiled, what few teeth remained showed unmistakably that I had made no error in bringing a present of a jar of "Rail Road Mills".

"Now, who be ye?" she said as she offered her toil worn hand. I explained as best I could the reason for my visit and after surveying me curiously, she started from the room. I sought to detain her and she replied, "I ain't got no time to be a foolin' long of you. I got to go out in the kitchen where sister is a gittin' dinner. She is run down in her manner this morning and I reckon I better go morter help her a leetle."

THE ROLL CALL

Turning to Miss Lucy, the sweet looking blond sister of 79 or there-abouts, who had met us upon our arrival, I asked her to tell me the names of all the family.

"I hain't got much time to set here", she replied, "I got to git that washin' done. I aimed to git it done before 10 o'clock, but that old mule got out and I had to go fetch him and I sorter got behind".

Imagine it! Seventy nine year old and doing the family washing! Not only that, but runningf down a recalcitrant mule.

Then she sat down upon the narrow boxed stair way which led to the attic and said "Whut wuz it you're a wantin' to know?"

"The names of your sisters and all about you", I replied.

"Well, I'll start at the oldest Julie yonder, she's eighty-three"

And at once Julie interrupted, "I took the axe one morning an' went out to chop some wood and arter I had been a choppin for about two hours, I come home and I couldn't hardly use this hand".

But Miss Lucy went on serenely, "Julie thinks that's wnut brought on her stroke, but I tell her 'hit woulder happened anyway".

"The next 'un is Mary Anna Lizabeth, but we call her Betsey, she's the one out in the kitchen agettin' dinner". She then pointed toward herself with the finger of a work hardened hand and said "I'm Lucy, I come next, then ther's Marjie, that 'un whut jest went out er hare to the kitchen and Cynthie, she's the baby."

Cynthie sat in her straight chair near the door which stood open giving a glimpse of the back yard and showed no sign that she heard her name mentioned. In her eyes was a lookk such as is seen only in the eyes of lonely mountain women or farm women in whom knowledge - her ample page, rich with the spoils of time, did never unroll. Women whose genial currents have been frozen by chill penury; who are, like the man with the hoe, bowed by the weight of centuries.

The front good opened and Miss Marjie returned followed by an old lady actually bent double with age and toil, her hair not yet quite gray and her eyes black and shrewd with the keenness of a mother tiger or an animal at bay and her eyes did not belie her tongue for it, like the old Uncle Remus told about, "Knew no Sunday".

"Howdy", she said and the grip she gave my hand felt more like the grip of a woman of 18 than 81. Giving me a look that was embarassing in its keen scrutiny, she asked abruptly "You haint's come here to make fun uv us, have ye?"

I hastily explained that I had come only to find out about their wonderful experiences, and their remarkable lives that I might tell others, saying, "I think it is wonderful that you five girls have lived here all these years without the help of any man and - "but, she interrupted proudly, "We hain't needed no man. I kin plow good as any man or split rails or do anything else that's a needin' to be done. Least ways, I could before I got sorter old. I hain't so much account now. I can't do no plowin' much, jest a lettle in my garden."

She looked at me with no hint of humor in her sharp eyes and added, "I bet you ain't never done nothing like that. I bet you're a lazy sort of a gal."

Laughingly, I admitted this accusation, which Mrs. Samons (who had accompanied me) said, "O no, she is not lazy, she is one of the smartest women I ever knew".

"Well, I bound you she wasn't smart til she got Old Man Have-To behind her", asserted Miss Betsey, vigourously.

Then changing the subject suddenly, she said, "You'll 'uv come ter a hospital here today" "I'm sorry you are sick", I said. "I haint' sick, I'm just down in my back today, just sort of low in my body", she replied and Miss Marjie, who was the best humored of the five, talking much and laughing a good deal, interrupted: "My back ain't what hit ought ter be. I hurt it about four years ago and it ain't been right since. I was a going along leading the old mule an a totin' a jug er water an I caught my toe - that there'ns right there (pointing to the toe of her left foot which was encased in a pair of men's shoes, with broad toes and flat heels, and laced up with a purple cord) - I caught hit in one of these here roots, you know how they pull you. I kept a pullin' a thinkin' it would turn aloose and it wouldn't turn aloose an the mule kep a pullin an the first thing I knowed, it had jerked me down. My back ain't been right since. Hit kept a gettin' worse an' I would er gone ter the doctor but I thought he couldn't do it no good lesses it was broke. I think I mighter jolted my kidney a loose.

"And another time I had put the mules in the pasture where they could graze and they got a nit fly after them an' they wuz a running round an' takin' on an' I went to cary him to the spring ter water. Lucy was leadin' one, we finally got there to the spring an' the fly got after them again and that 'un Lucy had wus cuttin' up so, I said "Lemme hold 'im an' while I was a takin holt er that bridle the one I had been er holdin' hit me some way in the back. I ain't never knewed whether he pawed me or bumped me with his head, but he hurt my back.

"An' another time, I wuz a goin' to cut wood - no let's see, I wuz a goin' ter the fiel to haul some grass and the mule run over one of these deep gullies and dumped me in the road an' when they picked me up, I couldn't hardly breathe"

"An' another time - " but Miss Betsey interruped "Stid er holdin' on ter the lines, Marjie helt on to the side uv the waggin".

"I been workin' on the farm as long as you, mighty near", said Miss Marjie, a little hurt at the aspersions cast by Miss Betsey. "I dropped punkin seed before my Paw went off ter War".

"We are all a gettin' sorter old now" said Miss Betsey, "We are so slow now it takes all day long ter git anything done. Take that fence out yonder, hit's been a needin' fixin' fer the longest, but looks like we just cain't ketch up ter git to it"

ROCKER WITHOUT ROCKERS

Miss Marjie interruped again, "I got a big load er manure needs ter be hauled out, but I cant life like I used ter could an' I been trying to git a Nigger to remove it for me, but he said after all these rains we oughter let the ground settle. I think it's plenty settled now, but they's a Nigger buryin' in the neighborhood somewheres an' of course I couldn't expect to get any work done under the circumstances."

"That is such a pretty bed", said Mrs. Sammons, pointing to the spool bed, and Miss Marjie immediately retored "Paw bought that there sted fer Jule when she was a growin' up".

Not to be outdone, Miss Betsey rose from her seat and walked across the room, her bent form swaying awkwardly, "I got the cheer my paw bought for me when I wus a baby" she declared.

"Hit wus a rockin' cheer, but hit's been knocked around so much the rockers is done tore off. Old Man Ben Merritt made that cheer, it was painted green but the paint is all done wore off."

Proudly, she displayed a child's size chair, hand made and pretty with a severeness which characterizes furnitue made by the pioneers. It was indeed worn smooth and devoic of paint from the handling of countless small fingers and the rockers were "tore away".

"Won't you get in it? she turned to the little girl who had accompanied us and her face lighted up as it had done at nothing else since our arrival. The child, about three years old, went at once and seated herself in the chair, but she evidently misjudged the height of the seat and sat rather hard into it.

"Ef you wuz glass, you sho wud er broke" laughed Miss Marjie but she got no answering smile, save from the visitors.

"How old is that chair?" I asked Miss Betsey.

"Hit's near bout old as me", she responded. "I'm a going on eighty-one and Julie's a goin on eighty three. Cynthie, there, she's the youngest and she is the grayheadest one of us all".

"Miss Julie doesn't look the oldest", I said. "She really looks like she might be the youngest of all."

Miss Julie smiled at the compliment and Miss Marjie laughed out-right. "She ought ter be the youngest lookin", she said, "She ain't got nothin' to do but jest set in that cheer, the rest uv us got to work".

"Yes", Miss Betsey spoke up, "I took off eighty little chickens the other day an' when I went out to feed 'em they wus five of 'em dead. A stinkin old rat had cut through the board and dug a hole up under the coop. Hit had been a "rainin" so the whole yard wuz in a loblolly, but I said "doggone you, I'll fix so you caint git in here again". An' I got a hold er some slabs that somebody had sent here for us to burn and I cut a plank and fixed it.

"Yes", Miss Marjie put in, "we have worked the farm and done all there was to do, and then when it was rainin' we couldn't work the farm, we wus a standin/ up spinnin' or weavin'. We used do a heap uv that, but hit got so we either had ter give up the farm or give up the weavin'. Hit wuz just too much an' I told Betsy that we'd just have to leave off some uv it. As we couldn't give up the farm, it had to be done".

"That is certainly a beautiful quilt on the bed. Did you spin that?" I asked.

"That there aint no quilt, hit's a coverlid" said Miss Betsey in a superior manner, putting a decided accent on the "lid".

"Well, it is mighty pretty whatever it is", said I rising and going over to the bed to examine it more closely. "Did you dye the threat for it?"

The "coverlid" was a handsome square design on black and lavender upon a natural colored background and was woven with the art of a Roy Crofter.

"Course I dyed that thread", said Miss Betsy with her voice full of scorn for all who would buy thread already dyed.

"I bought the dye for that there purle, hit wus this here analine dye or analeen dye whutever you're a mind to call it. But that black, I made myself out'n walnut hulls and He Pusley. You can't buy no black dyes that will hol". They'll every one fade out.

"What is He Pusley?" I inquired.

"Haint you never seed no He Pusley?" There was an unmitigated scorn in her voice. "You're seed Milky Pusley ain't you?"

I was obligated to confess I had not and she said witheringly: "You ain't never seed much have you?"

I admitted in shamelessly and asked if I might see her loom, saying that I had never seen any one weave and should like very much to watch her.

"You wouldn't know nothing bout it ef I was to show hit to you", she said. "You aint seed much. As I aint a goin to git it. I bet ef I was ter come to yo house and want ter see somethin' an' you wuz as tired as I am, you wouldn't want to git it"

I urged her, trying to be as good natured as possible, but she was adamant, "I ain't a going ter git it nor they shaint", was final.

While Miss Marjie endeavored to explain to my untutored mind the intricacies of a seven-star quilt pattern I let my eyes rove about the large room. Besides the two beds the room contained an old chest, nearly large enough for a coffin, the one rock er in which sat Miss Julie, seven straight chairs worn by time and much scrubbing to a smooth whiteness, and a small iron pot which sat in the corner beside the fireplace, obviously to heat water in. Over the door was a rude support made of branching hickory sticks, to hold the old fashioned muzzle loading gun. Beside the back door was a "water shelf" with the usually country bucket and dipper and wash basin. Underneath them stood a little wooden truck of the yellow painted variety of the gay nineties. Hanging in one corner was a saw and the four steps which showed before the stair turned to lead into the attic, were adorned with plant in old buckets, and boxes with snuff jars of varying sizes and with nondescript old pieces of quilts, clothing, etc.

THE WAR RECORD

I came back from my survey, just in time to hear Miss Betsey assert, "Thank God I am pore and thank God I was raised pore. I always have knowed how to work for my livin'. I ain't able to do much now, but I have done a heap in my time."

"Our father left us in sixty three and my mother died in seventy-one. After she died, there was some claim we couldn't stay here, just us five female girls with no man person. They wuz some talk about taking the youngest ones and I told 'em they weren't a going to do it. Ma had give me that baby (pointing to the white-haired 73 year old Marjie); and I warn't a going to give her up."

"I ain't able to work like I used to could. I didn't get the rest I need. I used ter wake up fo' day ev'ry nornin' but now I have ter wait for the chickens as "birds to wake me up. Some nights I don't git my rest. I don't git to sleep before 10 o'clock, I reckon".

"Did your father fight in the war?" I asked.

"Yes he wint ter the Civil War and he never did come back. He died with the jellow janders up clost ter Dalton".

Trying to be polite, and interested I said inanely, "Well, I declare, is that so!".

Leaning toward me with a rather angry look, Miss Betsy said "You don't think I'm a telling you a lie do you?".

I hastily reassured her and she went on. "I remember mighty well when the Yankees come here. The yard wuz just a work with 'em. One of them officers told Lucy to go to the spring to git some water and she wuz skeered to go. He said "Why don't you go on"? I said to him, "She's skeered, that's why". And he told her to go ahead and if any one of them Damyankees bothered her he's learn 'em how to bother her.

"So Lucy went and when she came back, she put the water inside the do, and I stood inside and reached the water to 'em in the goard.

"Shaw! I seed them Yankees when they wuz two miles from here. I said "The Yankees is a comin'", and Maw said "how her ye know?" I said 'cause I see that fire burnin' over yonder". The word had done been give out that they wuz a comin." An after a while, here they come, hollerin' and ridin' their hosses hard as they could. You could hear the water splosh in the creek half a mile off. I bet they rode them hosses cross that creek in a lope".

"Paw had a fine stallion horse and they took that off and he had a filly with a colt and they took them too. They killed Ma'e three turkeys and the chickens. An' I heared that over here at Mister Rich Garland's house, they poured all the syrup out an' walked all over the house just a poppin'' groun'peas an' throwing the hulls on the floor."

Much more conversation followed about the mules "a gettin' out", how good the missionary s'ciety in Hillsboro is about helping them now that they were not so young as they had been, about folks who come there a wantin' to see things an' a tryin' to buy things but Thank God they didn't have to sell nuthin' in their house yet and folks wouldn't want to give half what they was worth any how, and finally a cordial invitation to stay to dinner, which indicated to me that it was time to leave.

So I departed amidst many invitation to come again and dark hints on their part that I would never do it. Miss Lucy insisted on opening the gate so's I could drive in the yard to turn the auto mobeele aroun' and waved a kindly goodbye, but Miss Betsey was already back a gettin' the dinner and still low in her manners.

I drove away with my emotions in a turmoil as to which would gain the ascendency; laughter over the amusing expressions, tears at the pitiable conditions, sympathy for the gentle sister who sat so patiently in her chair of affliction, pain at the terrible tragedy of growing old and helpless. But overtopping all was my admiration for their courage, their hopefulness, their patient acceptance of the hardships which were theirs, their glory in it, the resentment they felt toward a pitying attitude and my large appreciation of the pioneer spirit which has enabled five women to make a living, however meager, and pathetic it may have been, out of the gullies and hills of a farm, and to be happy in spite of trials and hardships.

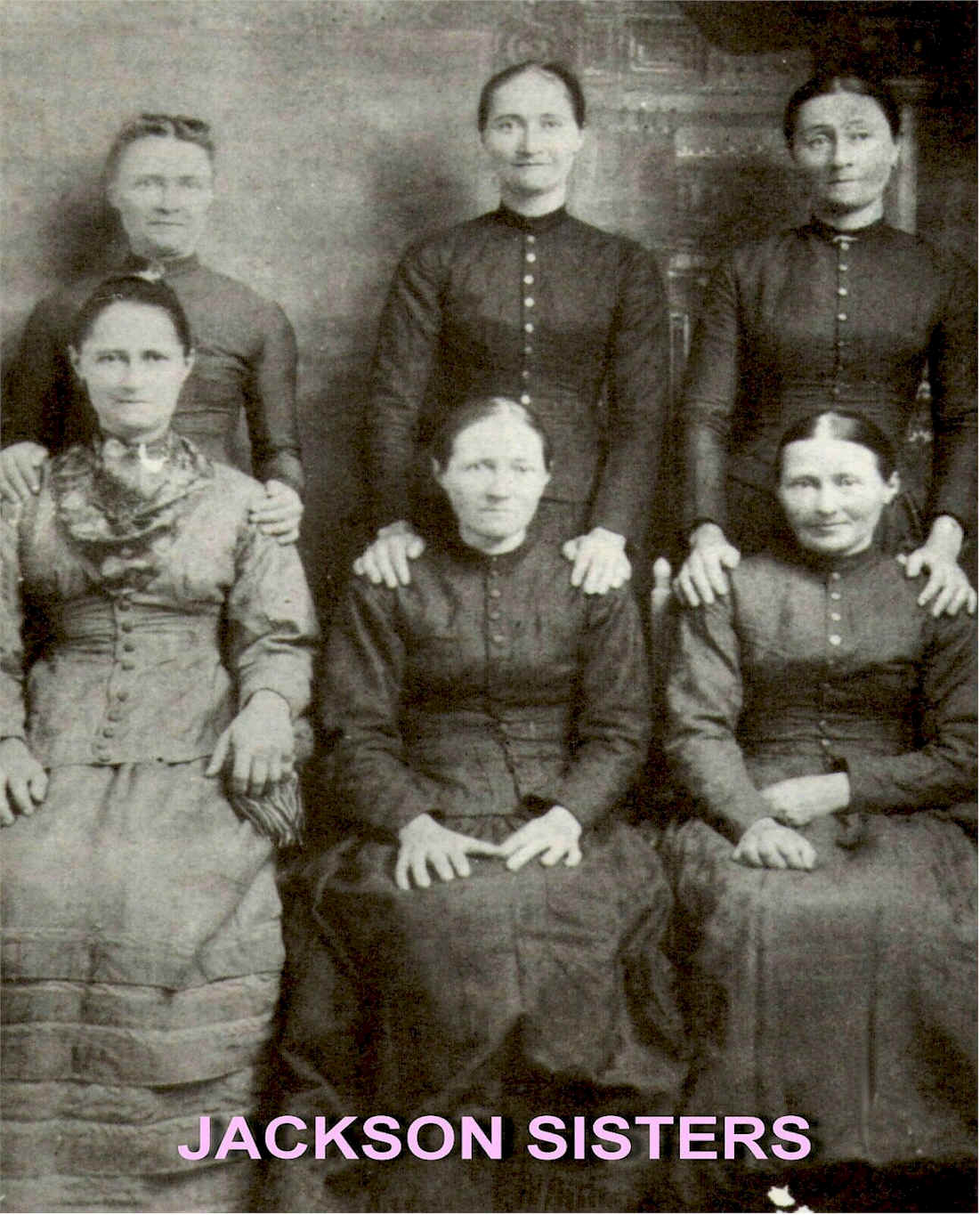

THE JACKSON SISTERS OF HILLSBORO, JASPER COUNTY, GEORGIA

ARTICLE WRITTEN SOMETIME AFTER 1940 IN THE MACON TELEGRAPH, MACON, GEORGIA

Jackson Girls

by Susan Myrick

Jasper County people still talk of the Jackson Sisters, six women whose father was killed in the early stages of the Civil War, leaving them, with their mother, to take care of a 300-acre farm. When their mother died, the "girls" continued to work the land, eking out a living much like their pioneer successors had. They refused to have the aid of any man; they plowed, hoed, weeded the cotton and cut their own firewood.

They spun the cotton and wove the cloth for their clothes, except for the calico they bought for their Sunday dresses. They spent their spare time piecing quilts, making comforters for their beds, embroidering elaborate patterns on the home woven cotton cloth to make bed spreads worthy of a place in a museum.

Youngest of the Jackson Sisters died in 1940, bequeathing all her worldly goods to Rufus Garland, a neighbor who had been kind to the Sisters during their good times and bad.

Mr. Garland, in his turn, bequeathed the Jackson possessions to his sister, Mrs. G. A. Wynnes, who has lived her days in Jasper County. She lives now in a white frame home at Hillsboro where ancient trees shade the house, and camellias more than half a century old blossom. It was my good fortune to spend a few hours at the home of Mrs. Wynnes, along with her next door neighbor, Mrs. Frances Reid and to wonder at the beauty of the craftsmanship of the Sisters, the quilts with their tiny stitches and pleasing patterns, the exquisite workmanship of the embroidered spreads.

One of these, made of home-spun and hand-woven cotton was embroidered with a replica of the American Eagle; it looked as if the bird had alighted from a Presidential seal. Above the eagle were 12 large stars and scattered over the spread were elaborate stylized designs, vines and shrubs, some of them looking vaguely like the Scottish thistle. The spread was bordered with a lacework pattern some three inches wide, ending in a handsome fringe.

We handled gently mementos in the old trunk the Sisters has left. Chief of these in interest was the yellowed paper that granted amnesty to the Confederate soldier, Andrew Jackson, uncle of the Sisters. The day brought very near to us the more than a century ago days of the War Between the States.

Transcribed by Suzanne Forte (suzanneforte@windstream.net) from information provided by Benny Hawthorne, December 2004.

INFORMATION ABOUT THE JACKSON SISTERS

Margia A. Jackson (mother of the sisters) Born Feb 27, 1822 Died July 20, 1871

JACKSON SISTERS

Julia Jackson Born March 25, 1847 Died Feb 20 1932

Betty Jackson Born Jan 2, 1849 Died Feb 16, 1935

Lucy Ann Jackson Born Nov 2, 1852 Died Dec 4, 1933

Margia C. Jackson Born April 6, 1857 Died Jan 9, 1934

Sarah A. Jackson Born August 23, 1859 Died Nov 25, 1916

Cynthia Jackson Born April 21, 1861 Died 19 March 1940

The Baby Brother was born July 6, 1863, died in two weeks.

The sister's uncle, Mr. Andrew Jackson died November 24, 1903.

*The above information was apparently written by Cynthia Jackson some time in the 1940's

The Jackson girls, their mother, and their baby brother are buried, mostly in unmarked graves, on their old home place near Hillsboro, Jones County, Georgia.

Transcribed by Suzanne Forte from information provided by Benny Hawthorne. December 2004.

MORE ABOUT THE JACKSON SISTERS

18 MAY 2012

(UPDATED JULY 21, 2014)

Submitted and researched by Suzanne Forte ( suzanneforte@windstream.net )

I submitted the photos, newspaper articles and other stories about the Jackson sisters of Hillsboro, Georgia, back in 2004, based on information and photos furnished to me by Benny Hawthorne.

Recently, I was checking the links on the Jasper County GENWEB site and noticed I was missing a photo that Benny had sent showing what remains of the Jackson sister's old home place. Of course, as usual, he promptly furnished that to me....well, that started my mind wondering what more I could learn about them.

From one of the newspaper articles, I noticed that they said their father went "off to war" and never returned. But they don't mention their father's name of anything else about him. Being a card carrying member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, I just could not let that go by without trying to learn more about his service to the Confederacy.

Not knowing anything but his last name was a challenge, but by 'backing into" census records I found him listed as head of household in the 1850 and 1860 census for Jones County, Georgia, 360th GMD, Whites District. The old home place, long gone now, is apparently right on the Jasper County line, but in Jones County. His name was Lewis Jackson, born in Georgia in about 1820.

Research of the Confederate Compiled Service Records and other information on ancestry.com and fold three shows that Lewis Jackson enlisted 6 Aug 1863 at Macon, Georgia, with Co C (later became Company D), 66th Regiment, Georgia Infantry, Captain Charles J. Williamson's Company, Nisbet's Regiment. He died 25 Feb 1864 , location not listed on Compiled Service Record. This unit was made up of men from Jones and Bibb counties in Georgia. Lewis Jackson is buried at Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta, Georgia. Information from "Atlanta, Georgia, Oakland Cemetery Records, 1773-1999" on ancestry.com, transcribed by Rachael Grizzle - in 1999, show a headstone for Lewis Jackson with a date of death as 24 May 1864.

In the 1850 census he is listed with his wife Margery A. age 26 and two daughters, Julia age 3 and Mary A. (Betty) age 1, also living in the household as laborer was Andrew Jackson age 33, Lewis's brother. (ancestry.com tree of the Cooper Family shows a marriage date of 14 April 1846 for Margery Ann Carmichael and Lewis Jackson)

One house away is listed a John Jackson, Sr, age 65 (born abt 1785), in Virginia, Martha age 23, Miley age 2 and John Haddaway, age 22, overseer, also an Elizabeth Mays age 25, these females are probably his daughters and grand daughters.Value of real estate owned as $5000.00. I am under the assumption, with no proof, that this is Lewis Jackson's father. (Update: July 21, 2014 - information from the tree of the Cooper Family on ancestry.com shows that Lewis's father is John Jackson (1784 - 1860), his mother Mary Polly Hammock (1777-1842).

In the 1860 census for Jones County, White's District, the following are listed: Lewis Jackson, age 41, Margina, age 40, Julia A., age 13, Ellen A., (Betty), age 11, Lucy A., age 7, Margia C., age 6, Sarah A., age 2 and Andrew (age 50) and Edmond (age 52) Jackson. Brothers of Lewis Jackson. Value of real estate $1000.00, personal estate value $800.00.

I have been unable to locate the family in the 1870 census, possibly because that particular census transcription for Jones County is very hard to read. More research is required. However, I do not believe this family ever moved from the homeplace.

In the 1880 census for Jones County, Whites District, the following are listed: Julia A., age 31, Mary A. E., age 30, Lucy A. T., age 28, Marge C., age 25, Sarah A., age 23 and Cynthia, age 21 and Andrew (uncle) age 61.

I located death certificate numbers and dates of death for Betty, Lucy, Margia and Cynthia Jackson from "Georgia Deaths - 1919-98".

The only death date that wasn't available when Cynthia Jackson made note of her sisters and mother's dates of birth and death was, of course, her own date of death, which was 19 March 1940, at age 79. I intend to request a copy of Cynthia's death certificate. (Update, July 21, 2014, "Georgia Deaths 1919-1998" on ancestry.com show Cynthia's date of death as 19 March 1940 in Jones County, Georgia, death certificate N. 7413, age 79 years.

There is a question of weather the Jackson's family farm was located in Jasper or Jones County. It has previously been listed as Jasper. According to the census it is in Jones County. White's district is VERY close to the Jasper County line. Note that the sisters in talking about the Yankees coming thru mentioned they saw smoke from the buildings in Hillsboro, that town is just north of the Jones County line.

Listed in the Jones County GAGenWeb site is a transcription of the Jackson Family Cemetery by Ken Smith. It is listed as being in the Piedmont Wildlife Refuge. Follow this link to the Jones County GAGenWeb page containing directions and list of burials.

NOTE: The Jackson Sister's Home Place is actually located in Jones County, Georgia (May 2012)